“The term ‘conspiracy theory’ has more to do with the relation of power, than that of people to truth.” - James Bridle

“A decent person doesn’t align themself with people who believe viral right-wing stories on Facebook over trained journalists, who think Q is real, who think the pandemic is fake, who think the earth is flat,” Internet personality @designmom tweeted in late August. The viral thread listed out many reasons why “decent” people don’t fall for conspiracy theories, why decent people would immediately see Trump as a “con man.”

Like many, I too treated people who believe in conspiracy theories as an errant artifact, in what seems a patronizing and misunderstood attempt to separate myself from thinking that didn’t feel rooted in “science,” in “fact.” To reassert, to myself and likely others, that I was the smart one. I wasn’t falling for this shit. But that’s an inadequate and unfair and ableist/classist portrait of a very complex situation, not to mention the fact that often these “fringe” ideas speak to immediate and felt discrepancies in power. In thinking about how we talk about people who believe in conspiracy theories, there’s usually a false sense of goodness ascribed to whoever is doing the onlooking. The idea that “decent people '' don't believe in these things, how “good” people aren’t fooled—that’s precisely not the point.

What’s driving people to this thinking isn’t always, or often, a need to be a certain way, a desire to do evil. It’s so often just a general need: a need to belong, to feel wanted, to feel like part of something. It is why so many people join cults and do not realize they’re in cults, why many of us have gravitated towards toxic people and friendships that did not serve us, but gave us something, brought us in.

In most of this newsletter, I’ll explore the rise of QAnon—a conservative movement that broadly believes liberal elites have a global pedophile ring that Trump is uniquely situated to challenge, and oddly not implicated in despite the dozens of women who’ve accused him of sexual assault and the fact he’s an openly proud rapist.

But let’s start with chemtrails, for they’re a good place to start in thinking about the plasticity of conspiratorial thinking. Some people believe chemtrails, the crisscrossing white vapor planes leave in their wake, are part of a sinister effort to control our minds and/or the weather. There are variations in the specific sects of this belief, but the gist is that chemtrails have a purpose that the public isn’t being told about. This theory picked up steam in the 1990s, making them perhaps the “first truly mass folklore of the network,” as James Bridle calls it in his book The New Dark Age.

“Chemtrails” are contrails, a mixture of vapor and CO2 and some other stuff. (If you want a better explainer check here.) But as Bridle explains in a long chapter about conspiracy, we are looking at something when we see these streaks in the sky, all of us, even if we interpret it differently. Conspiracy theories share a commonality, which is that there is a grain of truth in them—even the most seemingly absurd theories (to you, to someone) have a logic we can recognize, or can be linked to real discrepancies in power: our rapidly warming world, our decaying infrastructure and economy, the many well documented instances of the government spying on its citizens, the fact that it usually takes a whistleblower to reveal something of the sort. Chemtrails are man made. But why look to chemtrails when destruction is evidenced in the increasing severity of storms, the rampant wildfires that ravage the west coast, the worsening air quality and corresponding illnesses? Particularly in the U.S., climate change is a partisan issue—it is not simply looking at the burning world but who do we believe about why the world is burning.

ID: a photo of crisscrossing white vapor in the sky left by planes

Writer Anna Merlan has been reporting on conspiracy theories for years, and writes “for all of our bogus suspicions, there are those that have been given credence by the government itself. We have seen a sizeable number of real conspiracies revealed over the past half century, from Watergate to recently declassified evidence of secret CIA programmes, to the fact that elements within the Russian government really did conspire to interfere with US elections.” In this vein, Bridle calls conspiracy theories “a kind of folk knowing,” pointing to the same elasticity between the “official” narratives we’re told, the ample evidence that we’re not getting the full story, and the ones we make instead.

You may have come across QAnon thinking with the Wayfair scandal. A high-profile Qanon “influencer” spread the supposed gospel, which was then picked up by other forums and threads. The Q influencer noticed some cabinets on furniture retailer Wayfair went for way too much money, and that these were “all listed with girls' names," prompting followers to allege that the pieces of furniture actually had children hidden in them as part of a supposed child trafficking ring,” a BBC report on the situation states. Notably, more liberal people—especially on TikTok—have echoed the claims. It’s an easy claim to echo without challenging too deeply: even the most critical thinking person could retweet a “save the children” image thinking it aligned to what they knew about real-world abuse.

As Ali Breland writes in Mother Jones, this is the summer QAnon went mainstream, in large part because we’re all socially distanced and extremely online. We’ll get into the details, but I suspect a huge part of why QAnon thinking has taken off in these months of ongoing crises, in tandem with governmental neglect and revolution, is fear. As we’ll see, a lot of their more mainstream content has to do with childhood sexual abuse—which is real. QAnon has garnered support around issues which speak to real things, weaponizing the people who believe them in the wrong direction.

Breland also explains how QAnon is coming into further visibility: “Together, Trump and Fox News are perhaps the country’s two most influential conservative messengers, and their increasing public affiliation with Q is only one piece of a growing body of evidence that the conspiracy theory is now either mainstream or rapidly barreling towards it.” Trump recently said of QAnon: “Well, I don’t know much about the movement other than I understand they like me very much...These are people who don’t like what’s going on in places like Portland and places like Chicago and New York and other cities, and states. I’ve heard these are people who love our country.”

QAnon theories, like many modern conspiracy theories, were once relegated to more “fringe” areas of the internet, like 4chan and then Reddit, but have been pushed further into the mainstream as those platforms try to curb the rampant spread of fake news and hate speech. These ideas have since seeped into more “acceptable” modes of proliferation, finding buoyancy on the relatively unregulated worlds of YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and TikTok. Tech companies have been taken lightly to task for their role in radicalization, but the overall “neutrality” falsely ascribed to algorithms makes it difficult to pinpoint who, exactly, should be responsible for the slither into seeming technological autonomy, execs giving a bunch of shrugs as children are spoon-fed increasingly sinister bot content on their views-equal-profit sites.

Creeping into the “mainstream” also means political office besides Trump: A recent NPR piece notes “Research from the liberal watchdog group Media Matters for America counts 20 candidates for Congress who will appear on the general election ballot in November that have either identified themselves as believers in QAnon or have given credence to its dogma.” In Georgia, QAnon believer Majroie Taylor Greene won the GOP primary, getting praise from Trump on Twitter.

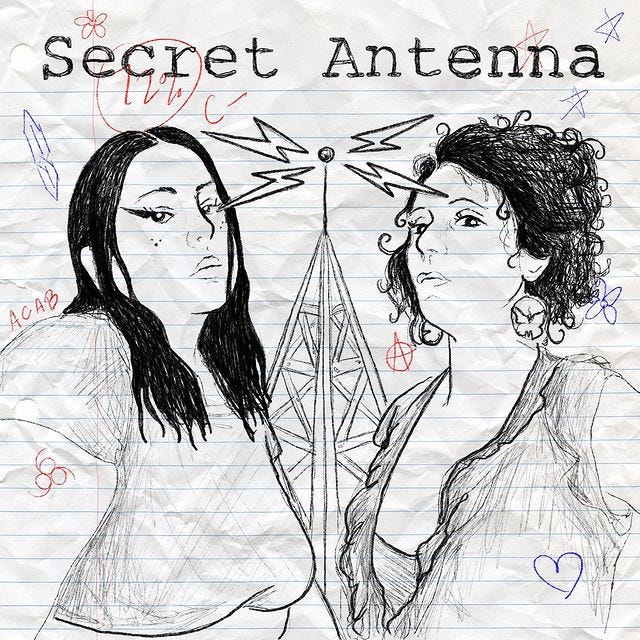

QAnon has led to real world violence, being cited in violent manifestos around the world. It led to Pizzagate, when an armed gunman shot into a closet of a Washington D.C. pizza shop, having been led to believe that Hilary Clinton and other high-profile democrats were running a child sex-trafficking ring from the basement. (In “lots of conspiracy thinking points to true horrors,” check out the podcasts TrueAnon which covers the Epstein case as well as the thinking around it in relation to conspiracy theories and Secret Antenna.)

When you look into how QAnon spread, it’s eerily (or, perhaps extremely expectedly) structured rather like an influencer trying to make it big. First, there’s the premise that the whole thing is like a game: looking for clues, discussing amongst one selves what may or may not be laden in the smallest crumb of non-information. It’s a play out of the handbook of Lost the TV show back in the day: a smidge of mystery isn’t enough, but the mystery combined with the potential that you could solve it may just be. It helps that social media, too, is gamified. Influencers depend on interaction of all kinds to stay relevant, such as posting inane questions to captions like “tell me about your favorite color” in order to trick the algorithm.

There are upwards of 700k posts tagged with “save the children” on Instagram. One page, labeled as “a cause,” has a well-worn Q phrase in the bio: “follow us down the rabbit hole,” accompanied by a white rabbit emoji. Most Q accounts use phrases like this, along with “keep digging,” and “free thinkers.” They frame themselves as being truth-tellers, poised to sift through the lies being told to them. Up to a point, it’s almost recognizable. But the irony of positing Trump as their savior though speaks to how effectively Trump uses similar tactics as Q: fear-mongering, sowing division, an emphasis on the good/bad binary in which he poises himself as uniquely situated to navigate. And with most of this information being disseminated on social media, a notoriously terrible place for nuance, the binary becomes further entrenched.

One screenshot of a tweet is pretty indicative of how a lot of Q content works: there’s a photo of the 2012 opening games at the London Olympics. The question says, “what does this look like to you?” followed by a photo of the coronavirus molecule. People see patterns—we want to see patterns, it’s a fundamental part of being alive. So while to me this makes no sense, it’s not a far stretch from the very common experiences of apophenia and pareidolia—the tendency for human brains to seek recognizable shapes, sounds, and meaning from what may be a random cluster of stimuli. Sitting in uncertainty is terrible, alienating, lonely. Most of us are apt to choose something, someone, some group, to help us make meaning of living in the anthropocene.

A fair amount of QAnon content look sort of like normal memes, or at least use the format of memes most of us would recognize. There’s one that’s the Spice Girls “if you wanna be my lover you gotta…” and the added phrase is “listen to me talk about the deep state all day.” One rather glam girl holding a “save the children” sign with the caption “we will continue to protest and make noise for our children” is asked “collab? DM us” in the comments by some rogue fashion brand. The comments discuss what may or may not be coded signals sent from “elites” or from fellow believers: why was Trump wearing a purple tie, what it means that Ellen DeGeneres showed a specific card from the deck. Having just spent a lot of time looking at how #FreeBritney gains traction, the techniques are not unrecognizable.

Rabbit Hole, a podcast from the NY Times, follows Caleb Cain, a young adult who narrates his radicalization. The show follows his YouTube search history in the years he fell down alternately alt-right and then very left rabbit holes—an amazing primary document into both the ideas that crept into Cain’s mind, and the algorithms that shaped those desires. In the beginning, Cain is lonely. He’s watching YouTube all day everyday, like many of us using media of some kind to be the background track to his day, to his life.

ID: Dali’s “The Persistence of Memory” which Shelby thought would be cool here for some reason. It’s a surrealist painting—nay, THE surrealist painting—with a blue and yellow sky and melting clocks draped over trees and desert landscape.

Caleb is shown increasingly further right videos—the more he watches, the more radical the suggestions. The automated reinforcement of ideas via technology is a central part of how radicalization happens so effectively online. Companies that depend on our views—and will continue to promote endless streams of content based on what they think we’ll like, or in lieu of knowing what, will hypothesize what we’ll want next—have rapidly accelerated the spread of what used to seem like “fringe” ideas. And at the crux of this: the algorithms integral to how this content spreads are not only treated as inhuman, implicitly neutral, but under that veneer of technological advancement they are literally designed, by people, to be addictive.

That you can’t log off your phone, that you feel your fingers reaching towards the just-so spot on your screen where your favorite app sits—this isn’t a personal moral failing. It’s not an inability to listen to the rainbow-hued post imploring you to stop scrolling and just log off. It’s being on the receiving end of feats of engineering designed to maximize the game that we, as users, aren’t intended to win. To these companies we aren’t even users: our attention span is the product.

Plus at this moment in time, when so many have been socially isolated perhaps for the first time, is logging off even feasible—emotionally? (I wrote about this last year, you can read here.) Networked community is vital—it can be healing, restorative, life-changing. That’s all still true. But how do we navigate to find our “people” when using websites designed to treat us as pinpricks of data?

In our daily networked interactions, these algorithms shape our reality, though we hardly are given the space to notice, so quick thoughts move, so inextricable we are from the deluge. On Twitter protests were trending for about two weeks and then promptly stopped appearing, despite the fact they’ve continued around the country. Fat people, trans people, disabled people, sex workers, Black women—all routinely have their content removed from searches and suggestions—not just by tech companies, but by policy, look at the EARN It act— while it often takes months or years of concerted organizing to get prolific fascists banned from social media sites.

I also don’t watch MSNBC for my news, nor do I want FOX. So like many I primarily use social media to follow news, specifically journalists. But I used to work in media, I feel relatively confident in being able to source things—I was trained how to do this, to an extent, and it’s still wildly confusing. To think how many people rely on social media only for getting news is terrifying, because among all the really important people talking and documenting what is happening around them, how do we know who to believe? We’re all looking at the same sky and seeing different things.

At least 18 percent of adults turn to social media to get their political news, according to a recent Pew study, and those people are less aware and less engaged in what’s going on. That same study notes, “Even as Americans who primarily turn to social media for political news are less aware and knowledgeable about a wide range of events and issues in the news, they are more likely than other Americans to have heard about a number of false or unproven claims.”

With that framing, too, it makes more sense not only that Caleb found his way into the silo he did, but that there weren’t necessarily visible alternatives. Suddenly things Steven Bannon says don’t seem so “out there” to Caleb, seeing as before he knew it he’s been brought in. A lot of the early topics in these videos are probably familiar—they’ve got corollaries in centrist spaces in the likes of Bret Stephens and other tenured men who hand-wave about college kids being college kids. Feminists, social justice warriors, identity politics, safe spaces—this is their bread and butter. While there are legitimate criticisms of these concepts, sure of course, let me assure you this is really never that, but a broad brush that paints all social consciousness in direct opposition to their identity, their American-ness.

When we try to talk about who “could believe this shit” it becomes a weird dance of trying to have empathy for vulnerable people who are taken advantage of but also not being a Nazi sympathizer. Let’s be clear, absolutely no Nazi sympathizing. I do understand why someone who is struggling, who is lacking infrastructural support to provide for themselves, who is undereducated, underfed, underpaid, would turn to silos full of similar people, expressing a valid concern that the world is unjust, correctly noting that power is concentrated to just a few.

It’s not surprising that one of the more prominent QAnon strains, “#SaveTheChildren,” has found a home outside the typical sort of “guy who got radicalized” image, Caleb Cain sitting in front of his computer all day, listening to Jordan Peterson. Save The Children appeals to the exact kind of audience Phylis Schlafly (we’ll get to her) would’ve drooled over: a newly awakening political mom, often religious, who can be shaped and molded to larger policy whims, disseminating these ideas among their silos. Save the Children has a fervor that is very much like the anxiety around the Satanic Panic (shout out to Sarah Marshall), wherein fear around unprovable theorems that still reflect real world disarray becomes the connective tissue of their community-slash-cult.

And in both the Satanic Panic and QAnon, there are children to save. Fear around children’s autonomy, weaponized by adults, has roots in panic around kids being trans, being gay, being disabled. At its core it is a eugenicist idea, wherein to preserve the supposed purity of the white children, they must be protected from the rapidly progressing world. General fear is rendered into a specific evil so as to flatten the good vs. evil binary. These misdirected efforts miss the actual abuse children are subject to—almost always from people they know, like family members. Perhaps some of the logistical backbending done to point at a secret cabal of pedophiles is to alleviate the fear that the actual monsters are devastatingly common, horrific in their normalcy and proximity.

Using children to dog-whistle about the destruction of the nuclear family, a supposed slipping from whiteness? Not new! The panic around children specifically mobilizing religious conservatives and suburban white women? Not new. It’s sinister, because while many Q supporters may be intentionally trojan-horsing more openly fascist ideas through the seemingly morally-net-good of “saving the children,” some clearly just think “saving the children” is all there is to it. This has led to a more diverse group of QAnon supporters, many who have the aesthetic of “socially minded person online.”

But the quasi-feminist angle on protecting children certainly has spread some of these ideas quickly, in part because of how effectively they look like your average well-intentioned infographic. In a fascinating article on The Atlantic called “The Women who Make Conspiracy Theories Beautiful,” Kaitlyn Tiffany writes: “Its supporters are so enthusiastic, and so active online, that their participation levels resemble stan Twitter more than they do any typical political movement. QAnon has its own merch, its own microcelebrities, and a spirit of digital evangelism that requires constant posting.”

Of course there are children we could help, and many people likely know or feel that. We could release children from immigration centers, from jail, from any number of other harms they encounter, for a start. The fervor around this is similar similar to a lot of harmful thinking about how to “save sex workers”—notably never by giving them money, homes, medicare, you know things that would actually help avoid the myriad of violence directed towards them—but by saving them from themselves. This ethos seems integral to the non-profit industrial complex and charity, more broadly: rather than look at the problem, it seems it’s often easier to create a meta-narrative that allows the onlooker to situate themselves as a savior poised to intervene. It may be easier to point to a global conspiracy than to look at what is happening in your own home.

A recent two-part deep-dive into Phyllis Schlafly on the podcast Behind the Bastards traces links between the conservative right, suburban white women, and an anti-feminist, racist, individualistic way of thinking. Schlafly was a 1970s conservative icon, particularly gifted at radicalizing bored or unfulfilled suburban housewives, training them to be political pawns, essentially. She harnessed the emerging religious right and focused their gaze on, broadly, opposing the Equal Rights Amendment and outlining the “threat of communism.”

It’s an eerie mirror to now. While more and more people were pushing for equality and belonging, Schlafly was able to form a community with these people who wanted to belong but didn’t know where, or how. The yearning to create a new type of family, especially with supposed threats to the nuclear family, seems to speak to the underlying need to be part of something, stemming yet again from fear.

While yes, white women across the political spectrum still are subject to misogyny, many—again on all sides—will cede to whiteness over gender. Schlafly actively worked against things in her own “interest,” which many retrospectives about her call irony. It’s not irony, it’s a well documented pattern of white women being crucial foot soldiers for white supremacy. “White women worked hard for the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, America First in the 1930s, the anticommunist crusade in the 1950s and the John Birch Society in the 1960s. They created their own organizations as well — the Supreme Court Security League, the Minute Women, Pro-America, Women for Constitutional Government, National Action Group and Restore Our Alienated Rights,” Elizabeth Gillespie McRae writes in the Washington Post.

There’s ample information out there to “educate yourself” on this history, how it repeats itself, how white women are integral to advancing political motives. With that framework, it might be easier to spot how the current moment is pulling from a very specific conservative playbook. But I hope these musings have made clear how untenable an ask that can be, when you’re asking undereducated white people who may work multiple jobs to just stop everything and read potentially very inaccessible sources about why they are the fools for trying to find adequate reasons to explain why everything sucks so bad in America.

Just like believing Satan is the problem was be a useful heuristic to funnel fear into a locatable and containable vessel, finding the one meme page that claims to have all the answers and more-or-less articulates your fear might be more feasible in terms of making sense of the world. That’s not great, it’s very toxic. But it doesn’t mean the person who doing the believing is bad. That binary, especially for those of us who don’t believe in QAnon, is not helpful to perpetuate. We don’t have to agree, or tolerate, or advance their cause—but to discount everyone who believes as being foolish is not helpful. It will not reach them. Especially for people who specifically believe they are “saving the children,” it’s likely not going to register if we rail on them for being evil, seeing as this cause drapes itself (by design!) in moral righteousness.

Brushing off QAnon as a fringe belief only fools believe is to deny its complexity, even to the people who believe it. It is to fail to articulate to others that it is not just one or two strange ideas, but a network of thinking that broadly moves to oppose social progress in the name of “restoring” the nuclear family, the gender binary, whiteness. “Make America Great Again” weaponizes the same sinister nostalgia, a nebulous pointing backwards as a way to outline a future—one that will not benefit those who believe in it, solely those leading the charge. The unsettling irony of QAnon is that many believers are railing against concentrated power as concentrated powers take advantage of their deep and real need.

When reading about conspiracy theories and how they spread, I am struck by how easy it is. How terrifyingly simple it seems. How all of us exist in some sort of rabbit hole, and that though there are clearly rabbit holes that seem more “correct” to me, the effectiveness of these should be challenged too. It isn’t something we can will away, merely live within. But how? For one, I suggest that we take conspiracy theories—and the people who believe them—very seriously. To discount these beliefs as something only fools partake in is undermining to everyone, it strips the ease and rationale behind why people believe in what may seem, to you, like outlandish garbage. A lot of people are led to dangerous thinking, and dangerous action. It is real, it is present, it is a dangerous threat to all of us, especially as the President continues to parrot almost verbatim what many of these alt-right figureheads say, and as more politicians with openly conspiratorial beliefs seek power, and continue to secure it.

Thanks for reading this long one! As always, feel free to email me with thoughts, questions, concerns @ awardsforgoodboys@gmail.com. I’m not an expert on anything, but hopefully could help steer you towards some new corners of thought.

A lot of my broad thinking about networks and algorithms is shaped from these books (I barely scratched the surface so, get in there if you can):

Algorithms of Oppression

Duty Free Art

The New Dark Age

Digitize and Punish

Also, if you’d rather go down your own journey, a suggested mini syllabus below:

The Summer QAnon Went Mainstream (Ali covers QAnon and is great!)

The Making of a Youtube Radical (NY Times) + Rabbit Hole podcast

The Women Making Conspiracy Theories Beautiful (from above but a good one)

Why are right wing conspiracies so obsessed with pedophilia?

Listen: You’re Wrong About on Child Trafficking

Behind the Bastards: Phyliss Schaffly

True Anon Podcast

How to talk to people who believe in conspiracy theories:

6 rules of engagement (The Conversation)

And then other things you should read and/or share:

Don’t Call The Police Dot Com — sources specific to where you live!

How tear gas may be wreaking havoc on protesters' reproductive health

DETAINED, DEHUMANIZED,DEPORTED: Inside the cruel bureaucracy of ICE's immigrant detention centers

A photo of my dog being a frog:

ID: a photo of Clementine sitting nice and proper on a little fake sheepskin rug. She’s glorious.

With love in these tumultuous times,

Shelby + Clem

This was a great read! With everything going on in 2025 this type of critical writing is a must 🫶🏻

Well worth the read! So glad you've got a newsletter to provide much more nuanced ideas than insta allows (although you do a mightily good job considering its limitations) ☺️